Empathy: A Guide To Enhancing Human Connection

In this article, I will share my top tips on how to effectively demonstrate empathy in OSCE exams and, more importantly, in clinical settings. The article also explores insights on empathy from Ari Javonhari, a second-year medical student from Hull York Medical School.

What is Empathy?

Empathy has many complex definitions, but it doesn't need to be complicated. Essentially, empathy is showing another person that you care about them.

Empathy can be demonstrated in a number of ways, both verbally and non-verbally.

Empathy vs Sympathy?

Sympathy is akin to feeling pity for someone, i.e. you feel sorry for someone as they are experiencing a bad situation.

On the other hand, empathy is not about showing pity but rather showing care. This could be done, for example, by listening to the person and reflecting back on what you see and hear.

Can you Learn To Be More Empathic?

Absolutely, as with most practical skills, you can develop your ability to show empathy. While some individuals have a natural knack for this, I've also seen many students enhance their empathic skills through the mere act of practising. But it shouldn't stop there, once qualified, you should continue to reflect on and improve your empathic skills. After all, being a clinician is all about lifelong learning and self-development.

Why is Empathy Essential in Consultations?

Empathy is your ticket to building good rapport. Think of it as a toolkit for appropriately managing the most challenging of consultations, such as breaking bad news or managing conflict. But it should also be a core part of every interaction you have with your patients.

If you have decided to work in a caring profession, isn't it your duty to be kind and compassionate? Wouldn't you expect the same from a healthcare professional if you or your family member were attending a healthcare setting?

Beyond this, the General Medical Council (GMC) expects clinicians to "treat patients with kindness, courtesy and respect" (Good Medical Practice, 2024). Empathy encompasses all of these areas.

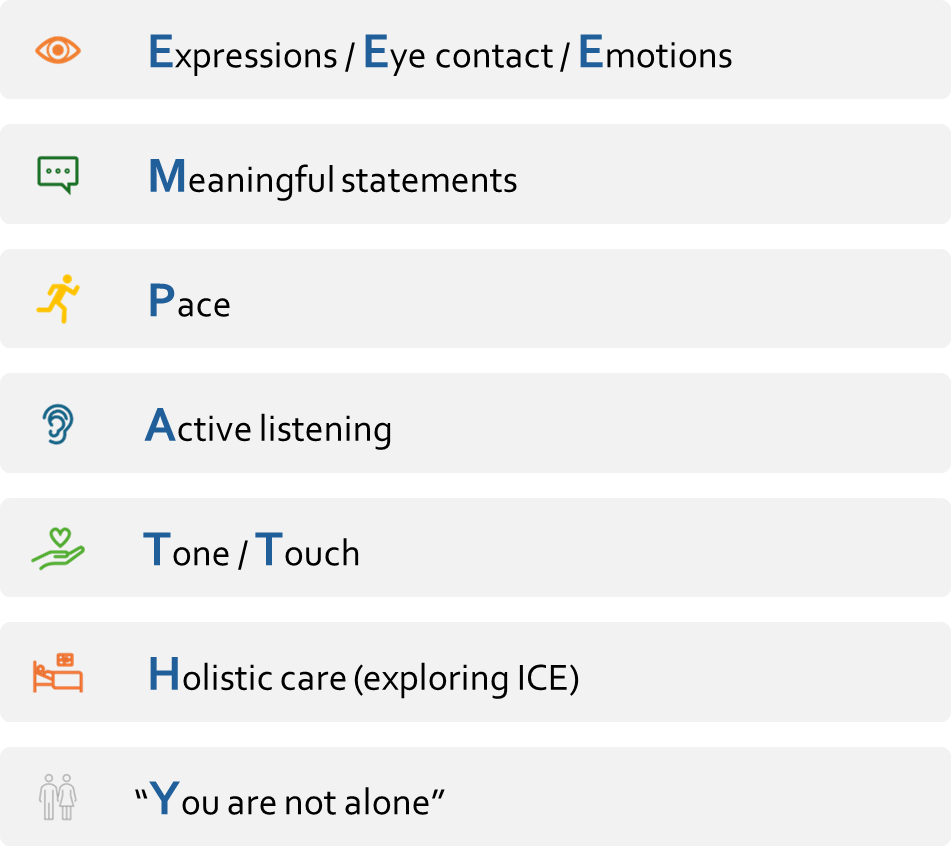

My Top Tips For Demonstrating Empathy

Try using my EMPATHY mnemonic to start thinking about how you can build more layers of empathy into your consultations.

Below, I have given further details on how using each of these key areas can help you demonstrate empathy.

Eye Contact

Maintaining good eye contact shows the patient that you are engaged in the conversation and not distracted. Many distractions exist in clinical practice, such as computer screens and excessive note-taking. We should be mindful of these barriers to communication and aim to position ourselves so that we can easily maintain eye contact.

Expressions

When your facial expressions are receptive to what the patient is telling you, e.g., you appear concerned when they reveal their concerns or alternatively show a smile when they discuss something positive; this will help your patient build an emotional connection with you.

Emotions

Picking up on and acknowledging a patient's emotions can be an excellent way to demonstrate empathy. For example, if a patient appears to be worried, we can acknowledge this by saying, "I can see this is worrying you." We can use the "Say what you see" strategy to acknowledge any emotion that surfaces for the patient. By acknowledging emotions, we validate them, and this helps to build rapport.

Meaningful Statements

These are statements that aim to convey your concern for a patient. Empathic statements need to be genuine in order for them to be meaningful and well-received. This means avoiding stock phrases and responding in real-time to what the patient is telling you. I'll explain this in more detail later!

Pace

Our consultations should proceed at a pace that is comfortable for our patients. If we generally speak quickly, a patient may feel as though we are in a rush, which can impact how they perceive our empathy. In particular, if we are discussing complex or sensitive topics, it is important to slow down, as this gives the subconscious message that you have time for your patient. On the other hand, speaking too slowly can, for some patients, come across as patronising, so essentially, there is a balance to be struck!

Active Listening

In order to listen attentively to a patient, we must ask open questions and give enough time and space for the patient to respond. We can use "facilitative responses" e.g., nodding, or using small sounds e.g., mhmm, to encourage the patient to keep talking and also to show we are engaged. During periods of active listening, we can also more easily notice patient cues. These may be verbal or nonverbal. We can then acknowledge and respond to the cues. Pauses and appropriate use of silence can also help convey empathy; these skills are often underused.

Tone

A soft tone, added to a meaningful empathic statement with the right pace and body language, can ooze empathy. I refer to this as adding layers of empathy into consultations. The more layers we can demonstrate, the more the patient feels cared for.

Touch

Touch, e.g., touching a patient's hand or shoulder, should only be used if this is judged to be appropriate to the patient and also if you feel comfortable doing so. For example, whilst working in palliative care, I recall touching a patient's hand when they were near the end of life. In this case, the patient had no family members or friends present. I'll never know, but I hope this brought my patient a sense of comfort; for me, it felt like the right thing to do, given the setting and context.

Holistic Care

Exploring the patient's ideas, concerns, and expectations (ICE) is an excellent way to show someone that you care about them as an individual. This helps us to understand what is important to the patient. If you need more information on this topic, I've written a separate in-depth article on how to explore patient perspectives.

"You Are Not Alone"

This is about ensuring that patients do not feel isolated in their healthcare journey. Even simply stating that they are not alone can help them feel supported. While we will not always have a solution for a patient's problems, we can always offer a listening ear.

Putting it All Together

During the pandemic, students taking their clinical exams were concerned about the fact that wearing a face mask might impede their ability to demonstrate empathy through their facial expressions. What was remarkable during this period was how eye contact (our eyes do say a lot!), empathic statements, tone and pace, when all working in synchrony, enabled these students to continue to demonstrate excellent empathy despite the barriers in communication. As already stated, the more layers there are to empathy, the more genuine it comes across.

More Advice on Empathic Statements (Let's Try to Change Them Up!)

As a communication skills tutor and clinical examiner, I have found that responding appropriately to empathic opportunities is often challenging for students, particularly in exam settings.

To give an example, let's say a simulated patient in an exam has stated that their partner died a few months ago. In this instance, students often have a default phrase they go to, and this can often feel contrived and lack authenticity.

The most common phrase I hear when trying to demonstrate empathy in these types of circumstances is:

"I'm sorry to hear that."

In essence, there is nothing wrong with the phrase itself, but if it is said as a knee-jerk response every time, it can be overused and lose its meaning. In addition, if it is not said with a soft tone and receptive body language, it doesn't feel genuine.

It is not only what we say but HOW we say it.

There are so many different verbal responses we could use in this case. Here are a few examples to illustrate this:

"I'm so sorry for your loss."

"It sounds like the past few months have been very difficult".

"How have you been coping since this happened?"

"Do you have much support since your partner died?"

NB: These phrases are not intended to be used verbatim but rather to give you a sense that you can respond organically in many different ways. There is no use in replacing one default statement with another!

Another area I often give feedback on is that simply saying an empathic statement and then quickly moving on to your own clinical agenda does not show genuine empathy. On the contrary, it can be perceived that your empathy is merely a tick-box exercise; clearly, there's nothing empathic about that! Empathic statements need time to land, and following this, you should respond appropriately to any patient cues.

If we are truly present in the consultation (and not worrying about what our next question will be!), we can use more of our senses to find empathic opportunities. We can watch for both verbal and nonverbal cues from our patients. We can respond in real-time to what we see and hear and, therefore, not rely on stock phrases.

The statement "I understand" can be a little controversial in the clinical context. I often hear this statement during communication skills sessions and wonder how it makes a patient feel. Can we really understand what they are going through? Perhaps we have been through something similar, but even so, our experiences may somewhat differ from the patient in front of us. On this point, I'm not convinced there is a need to share our personal stories with our patients. In my opinion, the consultation shouldn't take the focus away from the patient in a bid to show empathy.

I feel a more empathic response instead of "I understand" is "I can't imagine what you are going through." This change of wording seems to affect how it sounds and feels to patients and is generally well received.

A Sad Patient Story

Many years ago, I was talking to a simulated patient about his personal experience of receiving the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. At the time, he had attended a neurology clinic and was abruptly told of his diagnosis with no pre-warning. He described his clinician as having a cold manner and a matter-of-fact attitude about this incurable and life-changing condition. He discussed how he felt after receiving the diagnosis; it was a mix of shock and grief, combined with a sense of anger towards his clinician, who just didn't seem to care. He discussed how this made him feel like a number on a list rather than a human being. All of this had stuck with him, which was why he became passionate about helping train future doctors in communication skills. Bearing all this in mind, the next section will highlight some reasons why clinicians might not always be as empathic as they had once set out to be.

What Prevents Us From Demonstrating Empathy?

As humans, our ability to demonstrate empathy can be affected when we are tired, hungry, stressed, or under time pressure. All of the above affect clinicians on a day-to-day basis, and it is something to be acutely mindful of, as this can negatively impact how we communicate with patients.

Taking this a step further, we can consider the impact of burnout on empathy. Burnout is also sometimes referred to as 'compassion fatigue', meaning you lack compassion due to fatigue. In breaking bad news, for example, this disconnect can manifest in different ways. Maybe you're avoiding eye contact or speaking in a monotone voice. You might even find yourself rushing through the conversation, desperate to get it over with.

This is why it is so important to look after ourselves as clinicians both in terms of physical and mental health. The analogy is of the parent in an aircraft putting on their own oxygen mask before helping their child to do so.

If we don't look after ourselves first, we are less likely to do a good job of looking after our patients in a caring and compassionate way.

Views on Empathy From Ari Javonhari, a 2nd Year Medical Student From Hull York Medical School

"As a second-year medical student, I've come to realise that empathy isn't just a warm and fuzzy feeling; it's a crucial part of patient care, especially when things get a little tricky".

Next, we will explore Ari's thoughts on a few nuanced areas related to empathy:

- The Generational Gap in Empathy

- Fostering Cultural Compassion

- Empathy and Clinician Burnout

The Generational Gap in Empathy

So, you're cruising through your medical school journey; your university throws you out into the real world, ready to dish out some patient-centred empathy, right?

But wait, what's this?

The generational gap just threw a curveball your way. You've got patients from different walks of life, especially the seasoned ones, yep, the older generation. They might not be your usual Gen-Z patient who wants or feels the need to "let it all out" or talk about their emotions. So, what gives?

Well, here's the thing: conventional empathy isn't everyone's cup of tea. For example, some patients might not want to discuss their ideas or expectations and might even wonder why you are asking about this. Some older patients, for example, might prefer a more straightforward approach. They've been around the block, seen it all, and might just want the facts and your clinical opinion. It's easy to forget that these patients have lived through wars, lived to have seen technology change the face of the world and have seen the likes of 18 prime ministers come and go in their lifetime. It's a given that these patients had to be resilient to cope with those circumstances, so it's no surprise to observe the same attitudes cross over during your consultations…does that mean you kick empathy to the curb? No!

Empathy isn't just about giving patients a tissue or a shoulder to cry on. It's about understanding where they're coming from, respecting their wishes, and tailoring your approach accordingly. So, if Mrs. Smith isn't vibing with your style of empathy, no sweat! Maybe she'd prefer a friendly chat about the weather to break the ice, the key message here is not to take a patient's unwillingness to 'open up' personally, see it as an opportunity to explore and exhibit the many other facets of empathy.

The bottom line? Flexibility is your bridge here when it comes to closing that empathy gap. Keep your ears open and your heart in the right place, and remember, there are many different ways to show you care. If different patients have different expectations of the types of empathy they want to receive from their clinicians, it is our job to be receptive to this. There is no one-size-fits-all when it comes to empathy.

Fostering Cultural Compassion to Enhance Patient Care

There are many cultural, religious or personal reasons why our views might be different to those of our patients. A few examples of when this might come into play include:

- a patient refusing life-saving treatment

- a patient's lifestyle choices, e.g. alcohol intake, recreational drug use or sexual practices

- a patient's decision to terminate a pregnancy

Despite our own values and beliefs, it is important that we always communicate empathically with our patients so they do not feel judged for their beliefs or actions. This means being mindful of both our verbal and nonverbal communication and how this might make our patients feel. For example, our facial expressions, tone or indeed what we say, could potentially convey judgement and damage rapport with our patients. To avoid this, it is best to keep our questions and responses neutral when taking histories and discussing sensitive topics.

Picture this scenario, you're in the clinic, talking with your patient, and suddenly, they bring up a topic that hits a nerve, something morally against your own beliefs. Maybe it's something like abortion, and you realise your own beliefs might not align perfectly. It's one of those moments where you pause and think, 'Hmm, how should I handle this?'

Here's the thing - according to the General Medical Council's (GMC) current guidance on Good Medical Practice (GMP), we're expected to provide care that respects our patients' dignity and rights, regardless of our personal beliefs. But what happens if you find yourself in a situation where your beliefs clash with your patient's needs? Can you just pass them on to another doctor?

The GMC acknowledges that doctors have their own values and beliefs, but they also emphasise the importance of "providing care without discrimination or bias". So, while it's okay to have personal beliefs, we're still expected to put our patients first and provide them with the care they need.

With this said, there are some rare situations where it may be appropriate to refer a patient to another doctor if providing certain treatments/ideologies goes against your deeply held beliefs. This is known as a conscientious objection. It's imperative to understand that in these cases, the patient's care is not delayed or compromised and that the patient is treated with kindness and compassion at all times.

Empathy and Clinician Burnout

Is there a scientific link between empathy and burnout?

It is a complex and nuanced landscape where the lines between burnout and empathy blur and intertwine. But amidst this complexity lies an opportunity: an opportunity to cultivate empathy as a tool for resilience, prioritise human connection in the face of adversity, and reclaim our sense of purpose and fulfilment in the practice of medicine.

As medical students, we're no strangers to the pressures and stresses that come with the job. But how does all that stress impact our ability to empathise with our patients?

Research has shown that burnout can significantly impact our ability to empathise with others. When we feel overwhelmed and emotionally exhausted, it's easy to become disconnected from our patients, even when we're delivering difficult news or providing emotional support (Hojat et al.,2001).

But here's where it gets interesting: there's also evidence to suggest that demonstrating empathy can protect us from burnout. When we're able to connect with our patients on a deeper level, it can help us feel more fulfilled in our work and less susceptible to the negative effects of stress (Krasner, 2009). This suggests that fostering empathy in our interactions with patients could be a key strategy for preventing burnout and promoting well-being among medical professionals. Knowing this, surely the key is to master the necessary skills in conveying empathy.

Using Empathy In Other Settings

Fortunately, all of the skills we've discussed are transferable to any setting, including with your peers, work colleagues, family, and friends. So, isn't it worth investing time to build these skills and become more empathic? Especially as this can enable you to build better connections and more meaningful relationships with everyone around you.

Summary

- Empathic skills can be developed through practice and self-reflection.

- Using several layers of empathy in synchrony, e.g., appropriate empathic statements, tone, pace, facial expressions, etc., we can enhance how empathy is delivered.

- For empathy to be perceived as genuine, we must respond to patient cues in real-time and avoid default statements.

- We must adapt how we demonstrate empathy according to what each patient wants.

- Empathy can also be portrayed through a nonjudgmental approach. This is especially important when we do not share the same views as our patients.

- Empathy can enhance job satisfaction and reduce clinician burnout.

- The skills of demonstrating empathy can be transferred to any setting.

References

- www.gmc-uk.org/professional-standards/professional-standards-for-doctors/good-medical-practice

- Hojat, M., Mangione, S., Nasca, T.J., Cohen, M.J.M., Gonnella, J.S., Erdmann, J.B., Veloski, J. and Magee, M. (2001) The Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy: Development and Preliminary Psychometric Data. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 61(2), 349–365.

- Krasner, M.S. (2009) Association of an Educational Program in Mindful Communication With Burnout, Empathy, and Attitudes Among Primary Care

OSCE Course

If you liked this article, take a look at my OSCE course. I have broken down how to tackle different types of OSCE stations and included all my top examiner tips and advice. This is what I cover in the course:

- How to Prepare for OSCEs

- History Taking

- Information Giving

- Clinical Examinations

- Procedural Skills

- How to Effectively Summarise

- How to Answer Examiner Questions

- Worked Examples