Giving Information to Patients: How to do this Well

Information giving is a key aspect of many medical consultations and also a skill that can be honed before qualifying. This article focuses on questions that students have frequently asked about information giving and my top tips for ensuring you maintain a patient-centred approach.

Why am I covering this topic?

Most healthcare students are unlikely to get opportunities to practise information-giving outside of exam settings. Yet, they are expected to have developed these skills on day 1 of clinical practice.

As with any clinical skill, it is worth practising information-giving before qualifying. This will help you recognise areas for improvement and develop your own style. If you are lucky enough to have a clinical supervisor who is willing to allow you to practise these skills under supervision with patients, then that is ideal. If not, there are still many other ways you effectively can practise with your peers, family and friends.

#Remember you should not give patients unsupervised advice and information whilst still a student.

Information giving in clinical consultations

Information giving might include a range of different types of discussions, which might include some of the following:

Giving information in exam settings

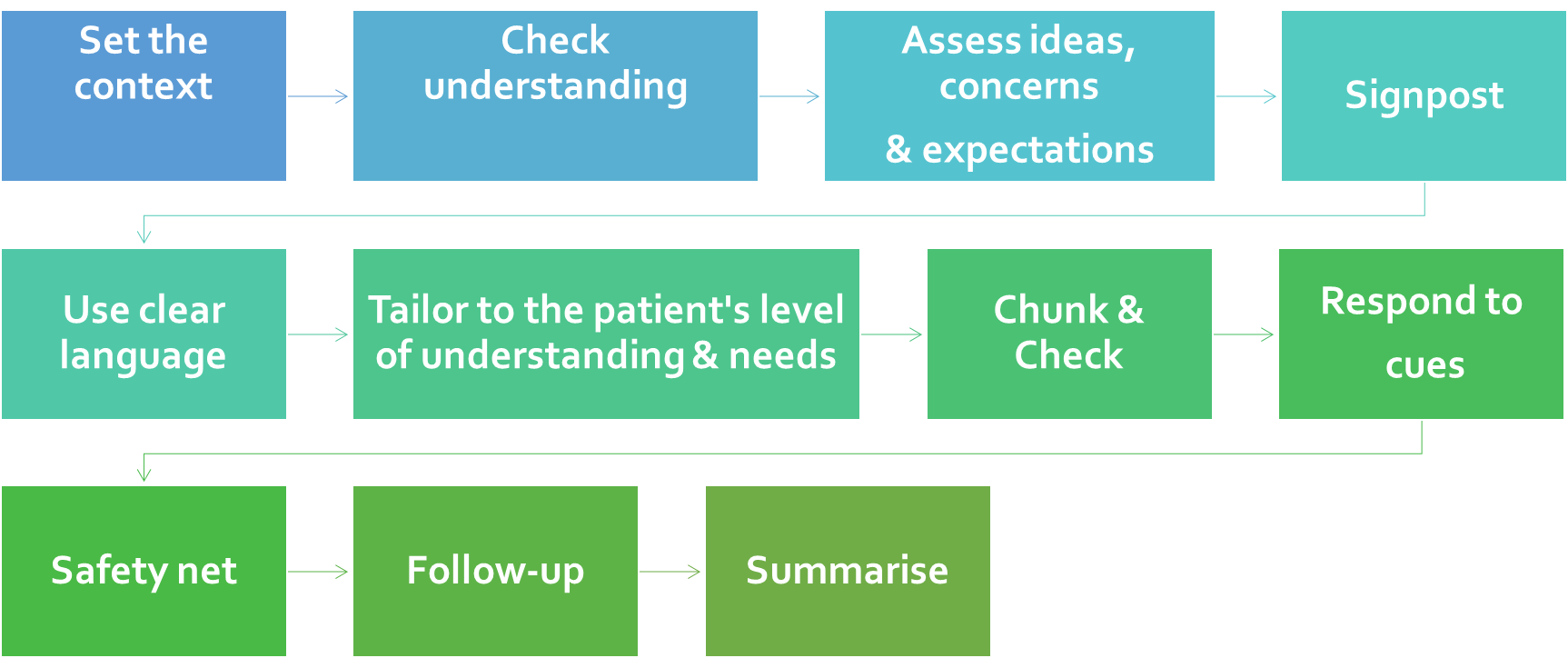

Information giving is commonly assessed in practical examinations. Students often find these stations challenging due to the time constraints. Maintaining a level of structure will help you prioritise your time more efficiently in both exams and clinical practice. This article will provide a basic framework for structuring these types of consultations. However, it is important that the framework is not applied too rigidly but somewhat flexibly to ensure a patient-centred consultation.

Starting the consultation

As with any consultation, clearly introduce yourself and your role. Then check the patient's details.

The start of a consultation is an excellent time to build rapport with the patient before delving into the rest of the consultation. A simple question such as "How are you doing today?" can ease you and your patient into the consultation.

To give context, in this blog, I will use the example of discussing the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes with a patient who has been recently diagnosed.

#Tip 1: Set the context of the consultation.

This is about giving an overview of what you plan to discuss.

"I understand you recently have been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. Today I would like to give you more information about your diagnosis and see if you have any questions. Then we can discuss the possible treatment options. How does that sound?"

#Tip 2: Give the patient permission to stop you and ask questions if anything is unclear.

Patients may feel embarrassed to tell you that they haven’t understood something, and in addition, they may not wish to interrupt you. You must offer your patients opportunities to ask questions and also pick up on non-verbal cues if it they appear to be confused.

"Please feel free to stop me at anytime if you have any questions or want further clarification."

Assess the patient's understanding.

You need to assess the patient's background level of knowledge about the topic. After establishing this, you can pitch your discussions at the right level. These are some examples of the sorts of questions you might want to ask.

"What have you been told so far about diabetes?"

"Are you aware of the main complications of diabetes? What do you know about these?"

"Has the management of diabetes been discussed with you? What do you know about the management so far? "

N.B. You may not necessarily ask all of these things at this point in the consultation, as this may fit more naturally elsewhere. Generally, as you start discussing new topics, you should assess the patient's understanding of that particular element.

Assess the patient's ideas, concerns and expectations.

"Do you know anyone with diabetes?"

"How do you feel since receiving the diagnosis?"

"Is there anything you are particularly worried about since receiving the diagnosis?"

"Let me know if there is anything you specifically want me to discuss with you today".

We can use all this information to tailor our discussions. For example, a patient might be particularly concerned about needing insulin injections. In reality, this might come much further down the line, or perhaps not at all. Alternatively, the patient's main concerns might be around the implications of the disease on their home and work lives. If we don't enquire about the patient's ideas, concerns and expectations, we cannot address these areas or empathise with the patient's perspective. Asking these questions provides a more holistic approach to the consultation and enables us to learn more about the patient's values and beliefs.

What level should the information be pitched at?

This all depends on the individual patient and their understanding so far. Perhaps they have a medical background, so using jargon would not be a problem in this case.

On the other hand, if you are seeing a patient with a learning disability, you might need to avoid using medical jargon altogether. However, you should recognise that there are large spectrums of patients with learning disabilities. Therefore, you should avoid making generalised assumptions regarding capabilities and adapt the consultation to the individual.

You might also be seeing patients that require tailoring of the consultation for many other reasons, e.g. patients with visual or hearing impairments or those whose native language is not English.

Be mindful that jargon may become 2nd nature to you, and you might presume that the patient has understood. It is essential to pick up on the patient's cues, e.g. perhaps they are nodding along, but their facial expressions appear somewhat confused.

#Tip 3: Practise scenarios with friends and family who have little or no medical background.

It is too easy to slip into using jargon and not realise it when working with peers.

#Tip 4: In most cases avoid using medical jargon or clearly explain it.

How much information should I give/what level of depth should this be in?

The key here is to give enough information so patients can easily understand and make informed decisions about their health.

#Tip 5: Start by giving an overview of the information and give more specific details if the patient wants to know more.

"Your recent blood tests showed some abnormalities with your blood sugar levels".

How should the information be given?

A topic should be broken down into smaller digestible segments, so it is easier for your patient to follow and also avoids overloading patient's with too much information. This process is sometimes termed "chunking".

We should also assess/ check the patient's understanding of the information at fairly frequent intervals. This process is often termed "checking".

#Tip 6: Use chunking

"The blood test (HbA1c) showed that the average levels of sugar in your blood over the past three months was high. This indicates that you have the condition type 2 diabetes."

"Diabetes occurs when your body can no longer control your sugar levels well. In this case, your body no longer responds appropriately to a hormone called insulin".

"Insulin usually helps to control the body's sugar levels".

Gradually build up the level and depth of the information. Ensure the patient has understood what has been said so far. This will generally depend on their background level of knowledge.

"In the long term, having high blood sugar levels is unhealthy for your body and can lead to complications affecting many different organs. These include heart disease, kidney disease, nerve damage and eye problems ".

#Tip 7: Be mindful of your pace when giving information. Giving large amounts of information, too quickly can be difficult for patients to follow.

#Tip 8: It is helpful to link back to symptoms the patient can relate to.

"The high blood sugar level explains the symptoms you have been experiencing, such as tiredness, weight loss, skin infections and frequently needing to pass urine".

The amount of information you give will depend on how much the patient demonstrates they want to know. For example, some patients might want to know every detail of their test results e.g. the normal ranges of HbA1c and fasting blood sugar levels, whilst others may prefer an overview of the results. You will need to figure this out based on the patient's cues and by asking them.

"Would you like to know more about the specific test numbers?"

#Tip 9: Check the patient's understanding at fairly regular intervals.

There is little benefit in just asking a patient if they've understood what you have said, as they will likely say yes, even if they haven’t. The way to know for sure is to ask the patient to repeat back what they have taken from the conversation so far. It is important that this does not come across as patronising or as a test. Instead, put the onus back on yourself.

For example, “Just so I know, I have been clear with my explanations, could you tell me about what you understand so far about diabetes?".

Alternatively, you could use the "teach-back method".

#Tip 10: Try using "teach back".

Teach back = An alternative method for checking.

"What would you say if you were explaining to your relative what we have discussed today?"

Moving on to discussing management

#Tip 11: Use signposting to shift the focus of your consultation before changing topics.

"Now that we have discussed your blood test results would you like me to discuss the treatment options?"

#Tip 12: A reminder to use "chunking" so the patient can easily follow the discussions.

"There are two ways that can help to reduce your blood sugar and hence reduce the chances you will develop the complications of diabetes. These include:

- A healthy lifestyle

- Medications

Would you like to discuss the lifestyle factors 1st? "

Discussing Lifestyle

You will need to take a focused social history to find out about the patient's lifestyle, so that you can advise them appropriately. For example if a patient does not smoke, we can instead prioritise other discussions.

"Before we discuss the lifestyle measures that can help you, I would just like to know a little bit more about your lifestyle. Can you tell me about your diet? What would you typically eat in a day? How about exercise? What do you do for work? Do you smoke? What about drinking alcohol?"

#Tip 13: Take a focussed history & tailor the information to the patient.

#Tip 14: Be as specific as possible with any recommendations.

"Based on what you have told me about your lifestyle. The main things that would help with your diabetes would be to:

- Reduce your portion sizes (see picture below)

- Increase your intake of vegetables, ideally five fruit and vegetable portions everyday. Ideally avoid very sweet fruits such as mangoes.

- Reduce the number of takeaways. Aim for this to be a treat rather than a regular habit.

- Reduce your alcohol intake, ideally, no more than one small glass of wine daily.

- Increase your exercise to 5 times a week for 30 minutes a day e.g. brisk walking or something else that increases your heart rate.

Do these suggestions sound like something you could do? ".

"Would you be happy to see a dietician to discuss your diet in more detail?"

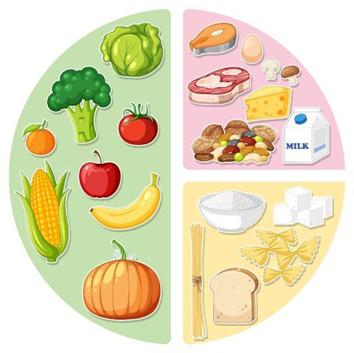

#Tip 15: Use visual aids and analogies

Pictures can often say a thousand words.

Use pictures, diagrams, test results, videos and analogies to help patients understand complex discussions.

For example, when discussing a balanced diet, you could show a picture such as the following to illustrate the proportions of vegetables, proteins and carbohydrates that would constitute a balanced diet.

Starting a medication

Assess for medical contraindications and allergies (take a focused history).

"Before we discuss the medications that can help control diabetes, I need to ask a few questions about your medical background and any allergies you may have."

#Tip 16: Assess any safety elements before discussing a medication start.

You could continue with the following discussions if the patient has no contraindications to taking metformin.

"We would recommend you start taking a medication called metformin to help manage your diabetes and reduce the chances of you developing any complications ".

"Have you heard of metformin?"

"Would you like me to tell you more about metformin?"

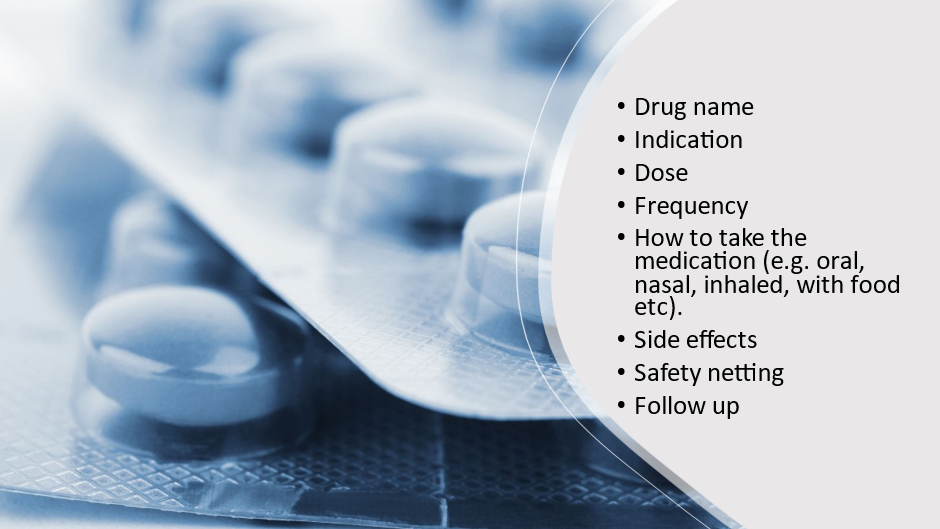

These are the key areas you need to discuss when starting any medication:

Drug name and indication

"Metformin helps to make your body more responsive to the hormone insulin. This helps to better regulate your blood sugar levels and will help to reduce the complications of diabetes."

Dose, frequency, how to take the medication and duration

"Metformin is initially taken once a day. You would take one tablet with breakfast every day for the 1st week. Each tablet contains 500mgs of the medication. We can see how you get on with that, but generally, the dose is then gradually increased over several weeks. Most patients remain on metformin for life."

Discussing side effects

Often students ask me about the level of detail they should discuss when discussing medication side effects. It is important to avoid overwhelming patients with endless side effects.

I would start by discussing a few common side effects and then follow this up with a few rare but dangerous side effects. It is important that you make it clear that the rare side effects are rare to reduce patient anxiety. A good starting point is using patient-friendly and medically sound websites to guide the level of discussions. My personal favourite is: https://patient.info

"The most common side effects of metformin are:

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Diarrhoea

- Loss of appetite

- Abdominal pain

- Altered taste

For most patients, the side effects are reduced by taking the metformin straight after meals. Many patients also find that these side effects subside after taking the medications for a few weeks."

If you experience any concerning side effects please inform your doctor."

"In very rare cases, some patients develop more serious side effects:

- Yellowing of the eyes and skin (jaundice)

- An allergic reaction

- Difficulties breathing

- A slow heartbeat

Please seek urgent medical advice if any of the above occur".

#Tip 17: Reminder: Don't forget to chunk and check regularly.

I have often seen students provide large quantities of complex information all in one go and then attempt to assess the patient's understanding at the end. Avoid overloading the patient with information. Instead, use chunking and checking.

Consider the key points you want the patient to go away with. Is the rest superfluous or necessary? An overview is often enough.

#Tip 18: Respond to patient cues

Does the patient appear confused?

#Tip 19: Use mini summaries

It is helpful to recap the key points using a mini-summary if the patient appears overwhelmed.

"Would it be helpful if I discussed how to take the medications again?"

#Tip 20: Make a shared care plan/ maintain a dialogue

Respecting patient autonomy is essential. Remember that patients with capacity, i.e., can understand, weigh up and communicate their decision, are free to make their own choices. It is crucial that the patient does not feel coerced into making a decision, even if you believe this to be in their best interests.

Information giving should ALWAYS be a 2-way dialogue. The patient should have ample opportunities to discuss their ideas and concerns and be offered opportunities to ask questions.

To maintain a patient-centred approach, decisions should be shared by discussing how a patient feels.

"How does this plan sound to you? How do you feel about the lifestyle changes and taking the medication?"

"Would you prefer to try the lifestyle measures first and then see how that goes for the next three months?"

"Do you have any questions?"

Safety netting and follow up

Safety netting provides patients with clear information about what to do in the worst-case scenario/s. In this example, here are a few things to consider:

- What can the patient expect from the treatment versus what side effects would be more concerning?

- When do they need to be seen again?

- Who should they contact if they are experiencing difficulties or problems with their treatment plan? When should they do this? (Immediately or can it wait until the doctor's surgery is open?)

- When do they need further investigations/blood tests/review etc?

In the case of a patient experiencing excessive side effects with metformin, they might be trialled on a slower release preparation, so it is useful for them to know that they should let their healthcare provider know about any difficulties with taking their medication. An appropriate follow up plan should be put in place to assess for side effects and adherence to the treatment plan.

#Tip 21: Safety netting is essential when giving information to patient's. Ensure the patient knows what to do in the worst-case scenario.

Summarising

#Tip 22: Use the last minute of the consultation to summarise the most important points.

Note that patient recall of information is best when this is done at the end of a consultation.

You may also wish to write down the key points, especially if there is a complex treatment plan.

#Tip 23: Provide further sources of information.

It is helpful for the patient to have a way to re-engage with the information after the consultation. Give an option that is appropriate to them, e.g. a patient-friendly leaflet, app or website.

Summary on Giving Information to Patients

This article aims to help you understand the key elements of communication skills when giving information to patients. N.B. The suggested phrases are not aimed to be used verbatim but rather so you can follow my thought processes and explanations. Please use your own phrases so your consultations do not come across as scripted!

New Course Now Available

If you found this post useful, you may like my Ultimate Guide to Breaking Bad News. It includes:

- An easy-to-follow 12-step process that will help you build confidence in breaking bad news.

- A handy mnemonic and detailed discussion on how to demonstrate clinical empathy.

- Advice on managing different types of emotional responses when breaking bad news.

- Discussions on how to tailor the delivery of bad news to different clinical scenarios.

- Lots of practical advice from me.

The Ultimate Guide to Breaking Bad News

Learn how to effectively break bad news to patients, taught by an expert.