Deconstructing & Demystifying the Review of Systems (ROS)

Most students find it challenging to integrate a review of systems (ROS) into their consultations. As a communication skills tutor, I have frequently been asked where the ROS best sits within a consultation, what to ask and how to make it patient-friendly. This article is aimed to help you build confidence in carrying out a comprehensive ROS whilst also maintaining a patient-centred approach.

What is a ROS, and why is it needed?

Let’s break it down. Essentially, a ROS checks several bodily systems to see if any pertinent information has not yet come to light during the consultation. You might wonder why a patient might not have disclosed symptoms to you, and there are several reasons:

- Remember that many GP surgeries in the UK actively encourage patients to discuss only one problem per appointment.

- Perhaps the patient is more concerned with other aspects of their health and wishes to prioritise these areas during their appointment.

- The patient might not have realised the relevance or importance of the symptoms. For example, a patient might not link their palpitations to the changes they are experiencing with their periods. This is an example where the patient might be suffering from undiagnosed hyperthyroidism, and in this case, the symptoms are very much linked.

How can I carry out a ROS that is patient-friendly?

When a clinician reels off a number of symptoms to a patient in an attempt to complete a ROS, it can all too easily feel like a checklist-style consultation. This can feel very doctor-centred. This is why it is important to avoid doing a ROS too early in the consultation. Instead, you should take a comprehensive history of complaint (HPC). This should be done using a balanced set of open and closed questions, allowing you to build rapport with the patient before you delve into a ROS. The ROS can also be done later in the consultation, e.g. following the social history, but there is no need to be too rigid with where it is asked.

If you have built a good rapport with your patients, they will then understand that you would like to ask them a series of questions and will generally find this reassuring that you are being thorough.

How to initiate a ROS

A helpful tip when beginning a ROS is to signpost that you are beginning this part of the consultation. An effective way to do this is by saying something like.

"Just to make sure I haven't missed anything, I'm going to ask you a series of questions."

Things to avoid when doing a ROS

- Avoid asking several questions all at once; these are called compound questions, e.g.

"Have you had any chest pain, dizziness or leg swelling?"

- Avoid leading questions e.g.

“You don’t have any leg swelling, do you?”

These two question styles can make it more difficult for a patient to answer accurately.

When should I do a ROS?

When taking a history, we should spend most of the time eliciting the history of presenting complaint (HPC). This should establish the bulk of the current symptoms and explore in detail the key systems that could be linked to the presenting complaint/s. The ROS should then be done once you have completed your HPC instead of mixed into the HPC.

How to do a ROS

Having seen hundreds of students attempt a ROS, the best advice I can give is to:

1: Start with a constitutional symptom review

Ask about:

- Fevers

- Weight loss

- Night sweats

- Lethargy

These generalised symptoms could be related to pathology in any bodily system. It is useful to ask about these in all consultations. The ROS should help you rule in or out pertinent positive or negative findings that will assist when creating your list of differentials.

2: Do a head-to-toe assessment to cover key systems

The most logical and efficient way to carry out a ROS is to start from the head and work your way down. You can, of course, skip out any systems that have already been covered in your HPC. Whilst a number of the questions will be closed questions, try to break this up with some open questions where possible e.g. "How have your bowel movements been recently?"

Try carrying out a ROS in this order:

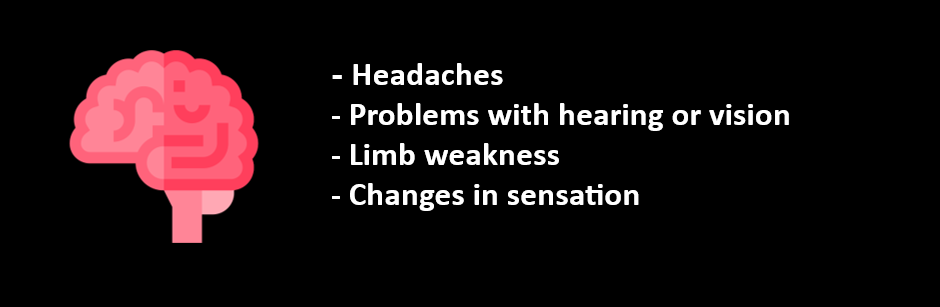

Neurological

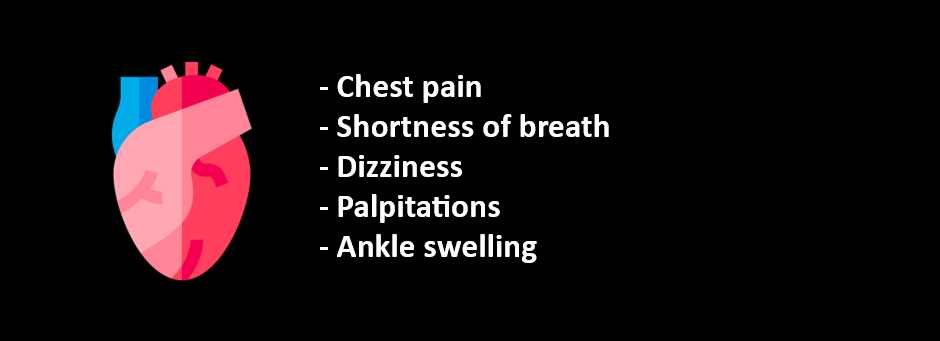

Cardiovascular

Respiratory

Gastrointestinal

Genitourinary

Endocrine

Musculoskeletal

Dermatology

Mental Health

NB. These lists are not aimed to be exhaustive but should give a sense of some areas you might wish to ask about in each system.

You will need to probe further if abnormalities are detected in any system. For example, if, on general questioning, you establish that a patient is suffering from a low mood, it would make sense to ask about suicidal ideation. However, you would not ordinarily discuss suicidal ideation with a patient who has simply attended with a sore throat unless something has come to light in the ROS or there is a relevant past medical history of note.

Another example would be if a patient reports headaches in the ROS, you would need to explore this further and ask about other associated symptoms, e.g. photophobia and neck stiffness.

Case Scenario

To demonstrate how the review of systems fits into a general consultation. Let's go through a case scenario.

Let's say a patient has attended with chest pain. First, you would establish the details of the chest pain in the HPC. You might use an aid memoir (e.g. SOCRATES) to ensure you have gathered all the relevant information about the chest pain. Remember to ask open questions as much as possible to elicit the history.

These are the systems to review within the HPC for this case:

- A full cardiovascular review, e.g. ask about the details of the pain and then continue to review other symptoms associated with the cardiovascular system.

- Respiratory review, e.g. chest pain, can be related to coughing or a pneumothorax for example, or perhaps there could be an underlying pulmonary embolism causing the chest pain.

- Gastrointestinal review, as conditions such as gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) can lead to reflux, which is often perceived as chest pain.

- Musculoskeletal review, e.g. has the patient strained the chest wall muscles at the gym that may be causing the chest pain?

Remember that all systems relevant to the presenting complaint/s should be reviewed in detail when discussing the HPC, whilst other systems can be reviewed later in a ROS. You do not need to ask about every symptom in a ROS but should briefly cover the core body systems.

Using the case example above, let's say the patient has also been suffering from prostatic symptoms for several months in addition to the chest pain. This could potentially be completely missed without a prompt in the ROS e.g. “Have you had any difficulties passing urine?” and hence, the ROS becomes an opportunity to explore symptoms that the patient has not previously raised. Whilst, in this case, the additional symptoms are unlikely to be related to the presenting complaint, in other cases, there might be an association that you had not thought to ask about during the HPC.

How long should you spend on a ROS?

- This all depends on the context:

- If you are under time pressures in an OSCE exam for example, a short and succinct ROS will suffice. I would suggest spending no more than 1-2 minutes in a 10-minute OSCE station, for example. In this context, examiners want to see that you know the importance of carrying out a ROS. Therefore, you should prioritise the questions you ask in this case. At a minimum, cover a constitutional system review and 2-3 systems that have not been included in the HPC.

- If you see a patient coming in with multiple or complex symptoms in clinical practice, a full ROS can help you narrow down your differentials.

Symptoms that require a detailed ROS

Certain symptoms can be particularly challenging to explore, for example, weight loss and fevers of unknown origin. In these cases, it is important to review several systems within the HPC to assist in making a list of differentials.

A Note About Focused ROS

In clinical practice, it is likely that a focused ROS might be done as a pose to a full ROS. This is an appropriate approach for experienced clinicians as they rely on their clinical reasoning skills to prioritise the information they ask. As a student, it is best to be as comprehensive as possible, especially when you have lots of time with your patients.

Summary

- A ROS is an essential part of a consultation and ensures you have considered broad differentials and explored areas that the patient might not have prioritised and yet might hold key information about their health.

- It is important to include the ROS at the right time in the consultation, i.e. when you have already built a good rapport with the patient, to ensure you maintain a patient-centred approach.

- A systematic approach, e.g. head-toe, ensures key systems are not missed.

- The more the ROS is practised, the easier it becomes to integrate it into your consultations.

OSCE Course

If you liked this article, take a look at my OSCE course. I have broken down how to tackle different types of OSCE stations and included all my top examiner tips and advice. This is what I cover in the course:

- How to Prepare for OSCEs

- History Taking

- Information Giving

- Clinical Examinations

- Procedural Skills

- How to Effectively Summarise

- How to Answer Examiner Questions

- Worked Examples